Valid and sound inference is a form of love:

On War, ignored evidence, and the seduction of shallow narratives

I’m not an expert in politics. But I am a systems engineer and a philosopher of science and technology - fascinated by how complex natural and social systems shape, and are shaped by, technological forces. Like many before me - Ursula Franklin, Norbert Wiener, etc - I began with building visible technical systems but became more drawn to invisible ones: the future narratives we share, the incentives we design, and the social assumptions we embed - because these shape not just how technologies are built and used, but whether they serve goodness and well-being at all. I’ve come to believe that if we get those invisible systems right - if we build more honest ways of knowing, more humane defaults, more thoughtful forms of care - then the visible technical systems would begin to become a force of global good. I believe that technology can help us see more clearly, act more justly, and become more intelligent creatures - not less.

I grew up in Iran and lived there until 2007. I was raised in a secular family that, like many others, stayed deeply connected to the wider world even as the political, economic, and social climate narrowed. Iran has had extremely deep cultural and intellectual ties to the West before the 1979 Islamic revolution, and those connections never fully disappeared, despite the Islamic Republic’s efforts to suppress or flatten them. In my experience, Iranian society has always found creative forms of resilience - an ability to maintain equilibrium, to resist, even in the smallest aspects of daily life. We all grew up on Japanese anime, American rock and pop, and global cinema. “The West” was never foreign to us - it was part of how we learned to feel and think. I’ve always been drawn to the strange intercultural mix that makes us humans of the 21st century: our flashes of rationality, our deep irrational impulses, our stubborn care, and our fragile hope for something better for the world.

I’m also not a US American. That gives me a certain freedom of experience and expression - a freedom to interpret events and people without needing to pick a side in someone else’s binary in a politically polarized environment. I watch both conservative and progressive media. I occasionally listen to Tucker Carlson’s interviews. I sometimes read leftist critiques. I don’t agree with many things from either side, and that’s the point. I find some bits of “woke” culture exhausting - especially when it reduces complex identities into slogans or it suppresses freedom of speech. But I’m equally wary of a world where people become so afraid of saying the wrong thing that they stop saying anything real at all. I hate arguments that cheer for war. I crave arguments that build something positive, a clever way of seeing and progressing. I feel most alive when someone shows a way of seeing the world and its events that breaks through the black-and-white, the radical contrasts. I like colors, not clear contrasts.

I was planning to launch this blog in a few months, with something very different. I’ve been working quietly on some exciting research about AI and the future of humanity—big questions, long arcs, and some surprising ideas I was excited to share when the time felt right. But life doesn’t always care about our timelines. Events erupt. Emotions build. And suddenly, waiting feels like avoidance.

So I’m starting here - not with my ideas about our future with AI, but with something more immediate, personal, and painful. I want to talk about Iran. About Iranians. And about the way the world has begun to talk about a war with Iran - with a stunning lack of complexity.

Last Friday, only four days ago, we woke up to war after Israel struck several civilian and non-civilian locations in Iran. And while many of us were still processing that reality - checking in with family, watching videos of evacuated neighborhoods in Tehran, of hospital walls shattered, of dead civilians - some of the world’s loudest voices were already moving on, making proclamations, performing certainty.

Here is a a post from Ian Bremmer whom I read quite often: an American political scientist and author, who is focused on global political risk.

This statement, I call it a shallow dangerous statement, might sound measured if you don’t care about the meaning of “far more support”. But if you don’t care about that, then you won’t have the capacity to judge its truth value. I have no idea why an expert on global political risk would utter such a statement. I want to share some evidence - and suggest resistance to the trap of shallow, dangerous statements of this kind. I believe Ian has been fed with one very specific diaspora ideology from the Iranian Opposition, a very controversial one.

Consider the Iranian opposition abroad - led, in part, by the son of the monarch overthrown 46 years ago: Reza Pahlavi. The revolution of 1979 was real. no one can question that. Its outcome has been truly tragic. But the exile politics that followed have their own strange detachment. Reza Pahlavi has lived in the U.S. ever since 1979. His daughters can’t speak fluent Persian. They call themselves princesses. They claim to represent a movement toward secular democracy, yet they cannot even form inclusive collectives with other Iranian opposition groups abroad - let alone build trust with the diverse political voices inside Iran. And yes, there are people in Iran who support them. But how many? Where exactly does this "far more support" come from, Ian? Because some voices are louder does not mean they speak for the majority. Volume is not evidence. Based on what balanced evidence you claim “far more support”? Who did you talk to? Have you listened to the millions of Iranians who explicitly reject the diaspora opposition? How do you weigh the evidence?

But to understand the abstraction Reza Pahlavi stands for - and the disturbing ease with which he promotes military intervention or downplay civilian casualties - just listen to this brief exchange on BBC from yesterday. Laura Kuenssberg is visibly taken aback by the evasiveness of Reza Pahlavi’s responses. Pahlavi doesn’t say 'yes,' but he clearly means it. His words are coated in abstraction while lives are on the line.

Writing about the Iranian diaspora - more than eight million people worldwide - is beyond the scope of this post, and I don’t claim to speak for its immense complexity here. But remember two things about the Iranian diaspora: First, the political imagination shaping much of that discourse remains frozen between two outdated poles— monarchy and theocracy. Between the ghosts of the pre-1979 Shah and the grip of the mullahs, too many Iranian disapora fail to even imagine a future beyond inherited binaries. Because it is a hard task. Second, Reza Pahlavi and his followers do not represent the majority of Iranians. They represent a particular narrative and a political nostalgia - but they cannot claim any meaningful majority support or democratic mandate. They don’t have any statistics and as I said they think about Iran of 2025 from their American experience of 1979-. I’ve attended several of their gatherings to better understand what they actually stand for. What I encountered was not a vision of participatory democracy, but a peculiar psychological attachment to monarchy - often expressed more as devotion to a symbolic father figure than as a coherent political program. Their volume does not equate to representative legitimacy or democratic majority support.

Independent of all that, I wish Ian Bremmer would have done his homework and balance evidence before uttering his consequential statements. Good reporting about “global political risk” should be grounded in complex understanding. Shouldn’t geopolitical commentary by vibe check be avoided?

Responsible commentary demands more than intuition; it requires grounding in legal, historical, and ethical complexity. Grand commentators are not there to pick sides - they are supposed to help the public make sense of complex phenomena without collapsing them into simplistic binaries.

Here is an actual expert, Marko Milanovic, Professor of Public International Law at the University of Reading, who writes:

"Israel’s use of force against Iran is, on the facts as we know them, almost certainly illegal."

(https://www.ejiltalk.org/is-israels-use-of-force-against-iran-justified-by-self-defence/)

If we don’t stand by international law, what hope remains for any shared vision of global cooperation?

The second journalist and media figure I want to address is Piers Morgan. I’ve followed some of his interviews and commentary on Israel and Gaza, among other things, and observed him shift his stance on various political issues, including his evolving assessment of Israel's actions in Gaza. I respect his commitment to uncensored debate - truth often emerges when opposing sides articulate their views with clarity and evidence - but too often, his framing slips into selective empathy: one side's suffering is centered, the other’s dismissed or downplayed. And when terms like “imminent” or “seems justified” are used without rigor, they shape public perception in dangerous ways. Piers is a sharp man. In moments like these, we should expect better - more caution, more clarity, more care.

A narrative is now circulating that Iran is targeting civilians while Israel is striking nuclear sites. This is, bluntly, false. And it is dangerous.

First, let me say this loudly and clearly: I’m deeply sorry for what Israeli civilians have experienced in recent days. No civilian - anywhere - should have to live through war, or see their neighborhood reduced to rubble and their loved ones killed. That kind of trauma leaves marks that words can’t erase. I grieve for every life lost and every life shaken by this conflict, on both sides. This war is a deep tragedy not just because of what is happening, but because of what could have been avoided easily. So many of us - Iranians, Israelis, and others - have spent years dreaming of futures beyond this cycle of destruction. We both deserve leadership that values peace over power, life over symbols, and diplomacy over military theater.

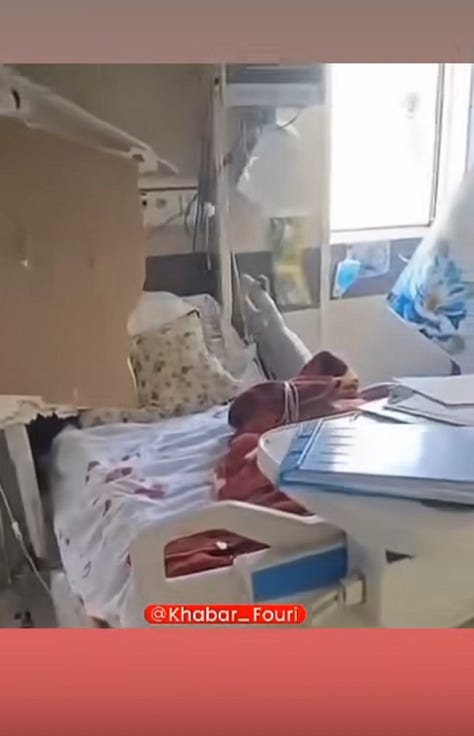

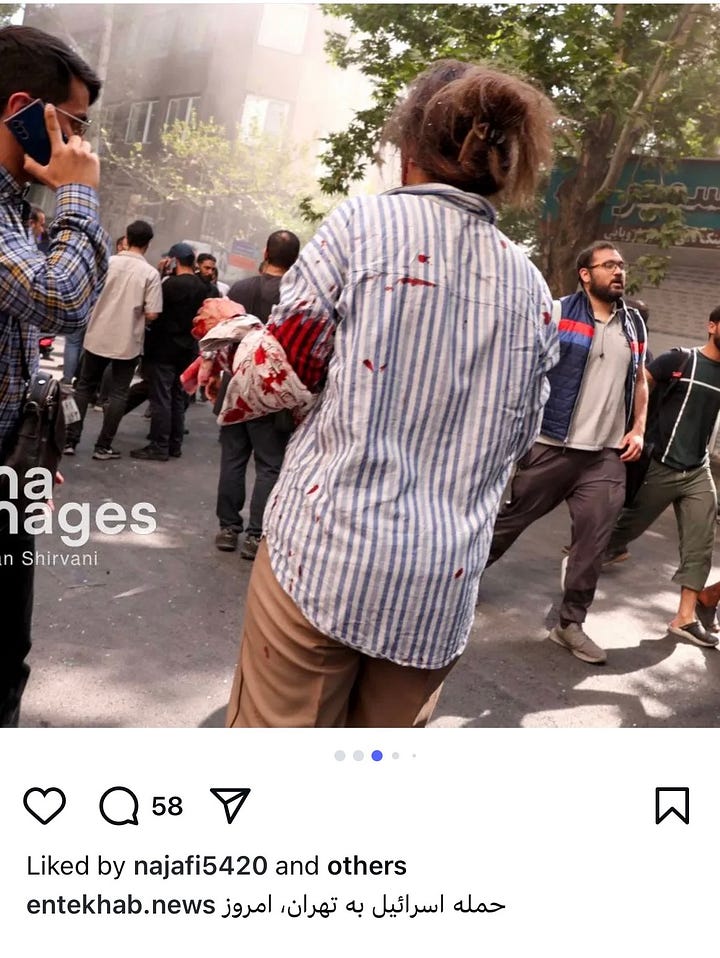

But let’s not cherry-pick the evidence. Both governments are targeting civilians. Israel’s military headquarters are in the middle of Tel Aviv. So when someone wants to attack it, they automatically have to attack a population center. We have seen many images of Iran’s targetting civilians. Such a tragedy. But let us also see only a few examples of Iran—images of hospitals, residential buildings, and public infrastructure reduced to rubble. These are not military sites or nuclear facilities. They are homes, clinics, and city streets. I’m sharing only a handful of images here, but we should be willing to confront all sides of this tragedy and to remind ourselves that we must oppose destruction itself, not just destruction committed by the other side. We must learn to hate violence as violence, not selectively based on the nationality of the victim.

In Iran, over 400 civilians have already died from recent airstrikes - many with no warning at all. This morning, there was an “evacuation alert” issued by Israel, and some of my Israeli friends expressed pride in the supposed morality behind it. But such an alert, issued without actionable logistics, is legally and practically meaningless- especially for the elderly, the disabled, the sick, and those stuck in traffic. You cannot ask a million people to evacuate a dense urban area and then claim moral high ground. That’s not moral care and protection; it’s performance. You cannot target Iranian media infrastructure and call it a nuclear site (As much as I never watch Iranian state media as I find it to be a propaganda media, but it is a civilian space.) You cannot strike neighborhoods and declare fair warning after the fact. You cannot frame this as surgical warfare when the bodies include children, doctors, families, and students—when destruction touches not only lives but also the cultural memory of a nation.

I acknowledge that millions of Iranians reject the Islamic Republic—and many of them are also deeply aware of the illegality and violence embedded in the actions of the Israeli government. Yet they are the ones now suffering most—trapped between authoritarian repression and a foreign war. I know that many of my Israeli friends feel similarly trapped—caught between fear, grief, and a leadership that too often mistakes force for strategy. I feel incredibly lucky to know many thoughtful, compassionate Israelis who, like many Iranians, yearn for peace.

None of what I’ve said excuses any government for targeting civilians, even if they claim to do so in pursuit of a so-called grand vision of peace. But it does mean that no side remains innocent when civilian lives are being lost. If we are serious about valuing human life, we must reject the normalization of war as a strategy. The only real path forward - truly forward - is through diplomacy. Through listening. Through restraint. Through voices like yours and mine saying: no more war.

Yes, the Islamic Republic has committed grave and unforgivable acts. Yes, many Iranians want it gone. But no war in the Middle East has ever produced the peace it promised. Not in Afghanistan. Not in Iraq. Not in Libya. So why repeat the experiment? Iran has nearly 90 million people. If you're serious about understanding them, start by listening to Iranians - including those who have stayed, those who have struggled, those who resist both dictatorship and destruction, and those who love the integrity of Iran, a country once the cradle of Persian civilization.

Thinkers and responsible journalists owe it to them - and to ourselves - to speak more carefully. Because in moments like these, valid and sound inference is a form of responsibility and human love. We should all be cheering for diplomacy, not destruction. No more wars. No more dead civilians. No more erased cultures. Our goal should not be to pick a side when both sides are to be equally blamed, but to stop the mutual destruction. We must be louder in our demands for restraint, for dialogue, and for the hard, necessary work of peace.

So: do not cherry-pick the evidence. Both governments are targeting civilians, and this war must be stopped as soon as possible on the basis of impartial evidence, not allegiance or noise.